The Keys to Perfect Boiled Eggs

I’ve spent a month researching and experimenting with the simplest cooked food there is - the boiled egg. The perfect boiled egg has two qualities: the yolk is the exact texture you want and it peels effortlessly. To get this you need to get the three T’s right: Type, Time and Technique.

The Type of Egg

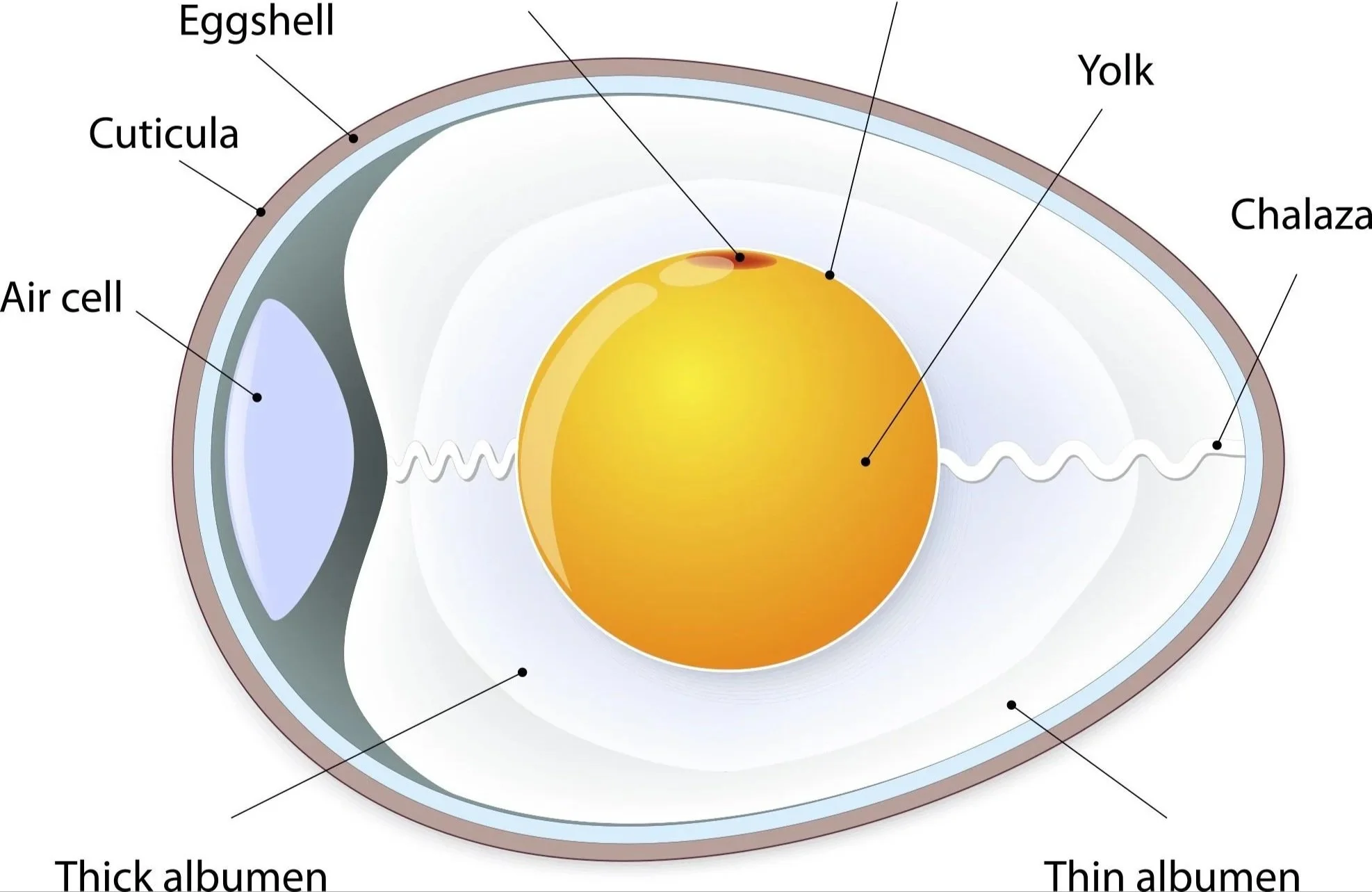

First, a quick refresher of egg anatomy. From the outside in, the egg has a hard, porous shell, two membranes that hold an air pocket in the wide end, a watery outer albumin (white), a thicker inner albumen, and a yolk. The white is mostly water and protein while the yolk also has fats.

As eggs age, gas transfer through the porous shell increases the size of that air pocket and there is more of the thin outer egg white. These changes actually make older eggs easier to peel than fresh eggs after boiling.

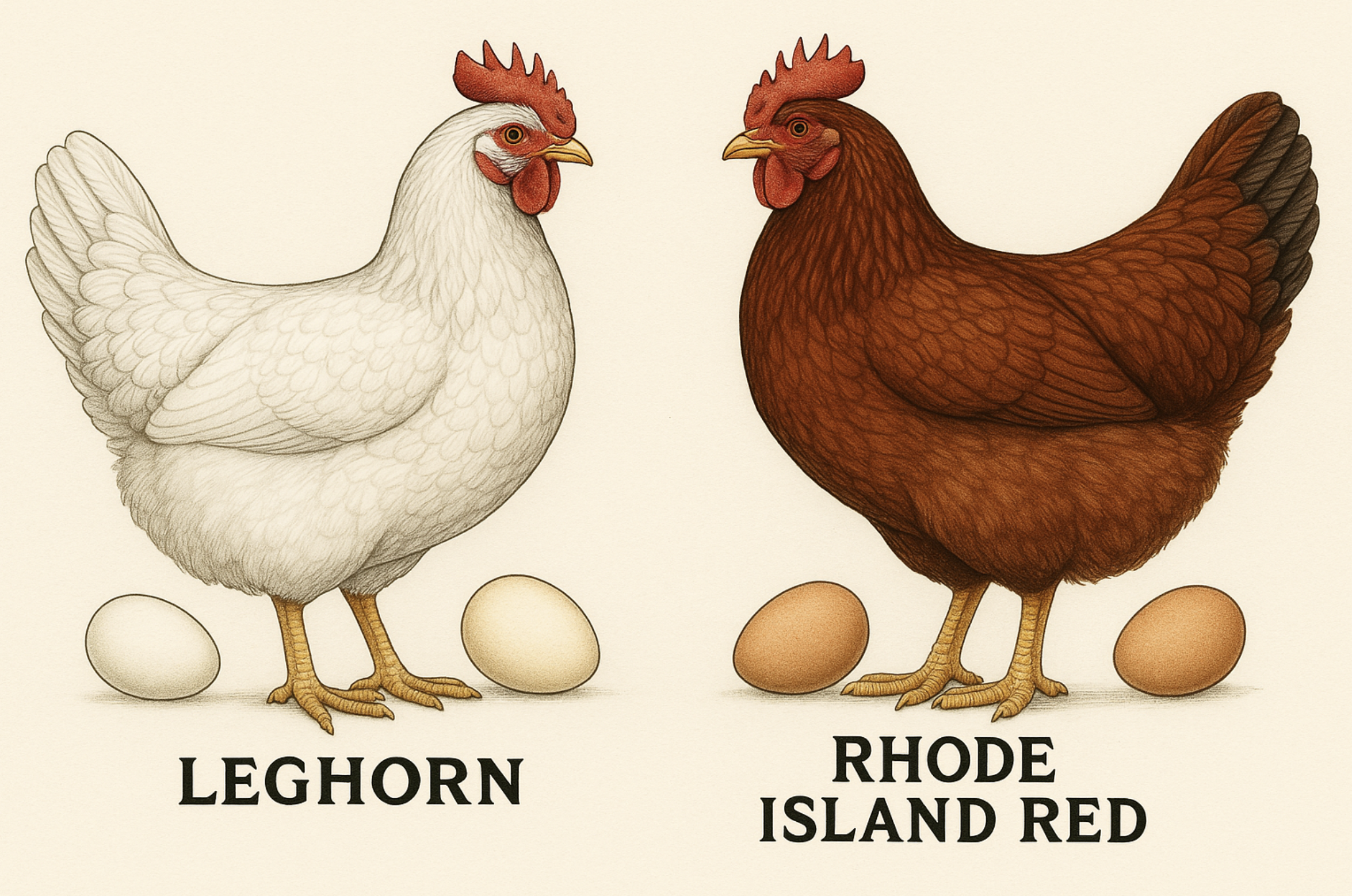

Eggs at the store are generally distinguished by size, color and farming method. In the United States, commercial white eggs come from the Leghorn chicken. It is a small, efficient bird that lays upwards of 300 eggs per year and requires less feed per egg than other chicken breeds. For these reasons it is the chicken of choice for Brown eggs that usually come from larger breeds or modern hybrids related to the Rhode Island Red. They often cost a little more and sometimes get to the shelf sooner, since they’re more likely to come from smaller, regional producers. Additionally, the pigment in brown eggs acts as a slight strength enhancer for the shell. With all else equal, a brown egg will have a slightly more resistant shell than a white egg.

The size of the egg has a direct impact on the thickness of the shell and the strength of the shell membrane. Younger hens lay smaller eggs with thicker shells and stronger membranes. When boiled, these membranes cling to the egg white and make it harder to peel cleanly. As the hens age, they produce larger eggs with thinner shells and less clingy membranes. This makes jumbo eggs noticeably easier to peel than medium eggs.

To put it all together, the best egg to buy, specifically for boiling, is a jumbo white egg. If your eggs are farm fresh, the color does not have the same importance. Fresh eggs will be tough to peel. The optimal age of an egg for boiling is about two weeks, up to four, after it was laid.

The Cooking Technique

The key to easy peeling is setting the outer white as quickly as possible. The faster it sets, the less time it has to bind to the shell membrane. In theory, the best method is steaming. Steam is able to instantly inject a lot of heat into the eggs. Condensing steam into one drop of water on the shell of the egg releases 5 times the energy of that drop cooling down to freezing.

In practice, this is difficult because opening the pot to add the eggs lets most of the steam escape and it can take up to a minute to rebuild that steam. The most practical stove top method is to drop the cold eggs, gently, into water that is already at a rolling boil. Use enough water to cover the eggs, keep them in a single layer and put the lid on to prevent the water temperature from dropping.

The Cooking Time

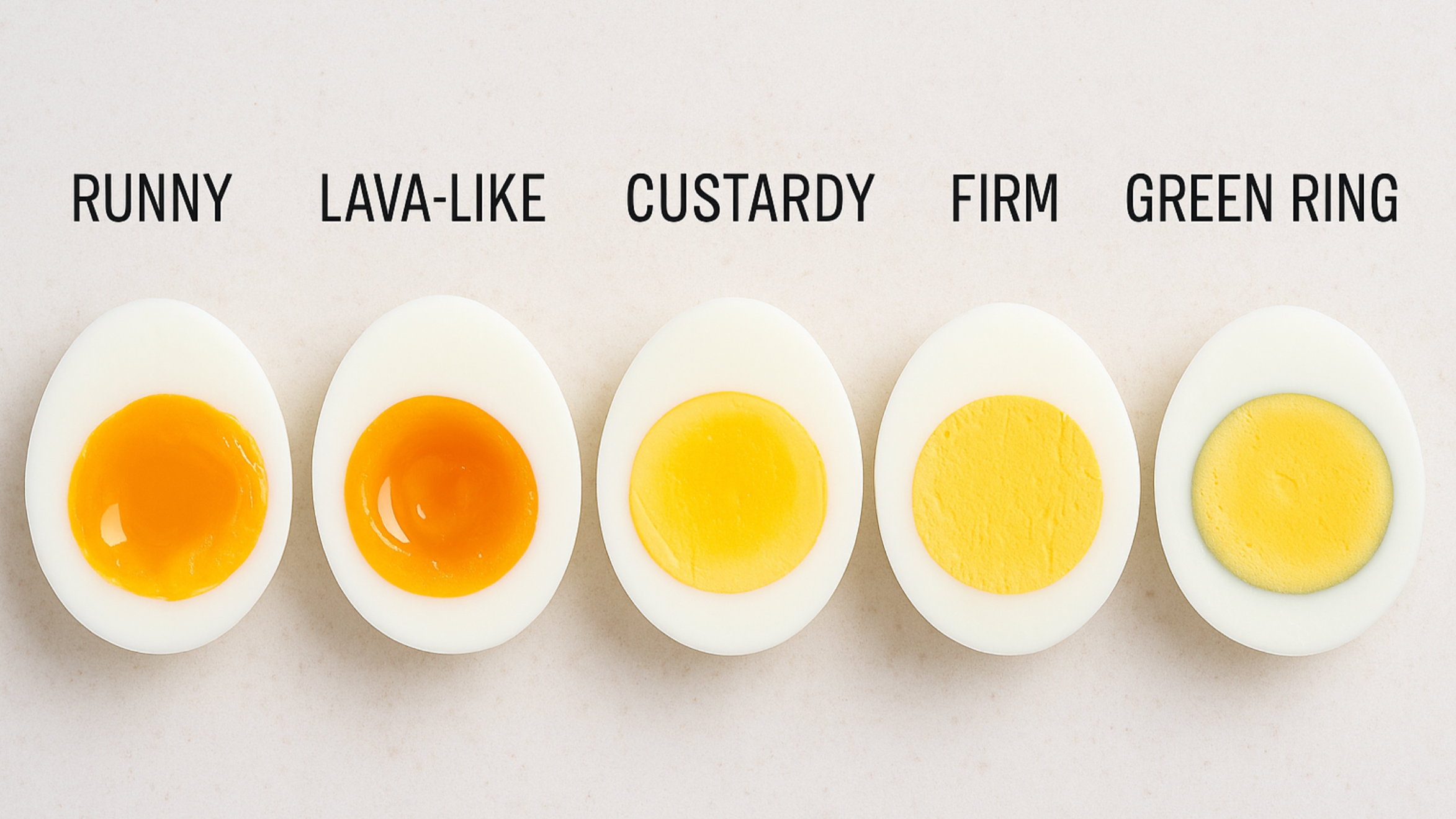

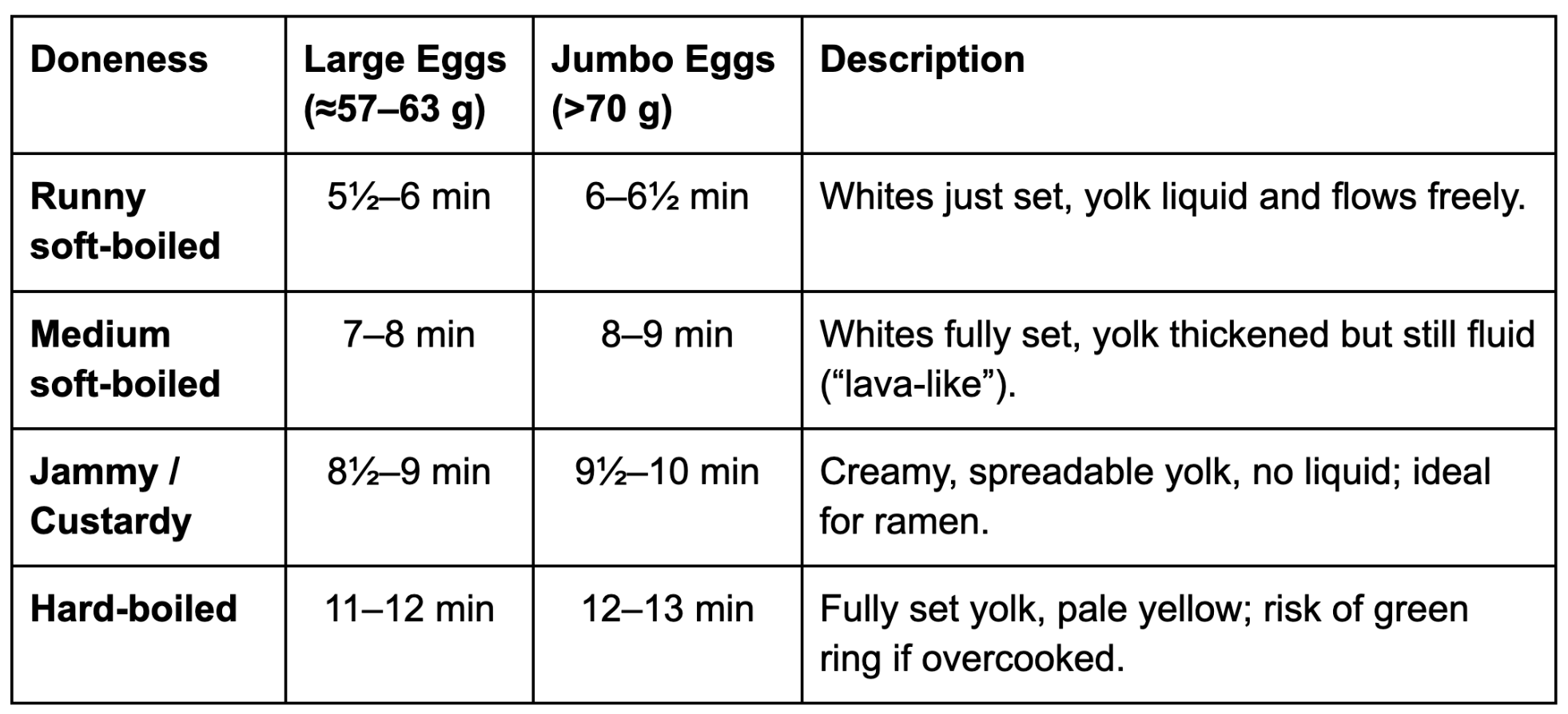

Cook time is what determines the yolk texture. Straight from the fridge into boiling water, the yolks pass through four stages: runny, medium, jammy, and hard. Each stage is simply a reflection of which proteins have set as the temperature increases.

In the first minute, the watery outer white sets. The first proteins in the egg white start to denature around 140F and transform the white into an opaque gel that holds water and gives the egg its structure. Over the next 2 to 3 minutes the thicker inner white follows. By the 4 minute mark the full egg white has set while the yolk is still liquid, just starting to warm.

From 4 minutes to 12 minutes, the meaningful changes to the egg are occurring in the yolk. Unlike the white, the yolk is an emulsion of fat, protein, and water — so it firms up in stages as different fat and protein interactions are altered by the temperature.

The yolk reaches 145F at around 6 minutes where HDL lipoproteins are among the first to denature. These form a weak gel network, trapping water and thickening the yolk. It changes it from a liquid yolk to a runny, lava-like consistency.

Around 155F the LDL lipoproteins denature and begin to solidify the emulsion. This starts around 8 minutes, creating a jammy, soft texture that is not yet solid but it is no longer a liquid. This would be a medium boiled egg with a spreadable yolk, also perfect for ramen .

After about 10 minutes, the temperature of the yolk crosses 165F and the more heat stable phosvitin denatures. It forms cross links that firm up the yolk and squeeze water out, making it drier and crumbly. This is the classic hard boiled egg.

If the yolk is taken past 175F, usually anything more than 12 to 13 minutes, the proteins over coagulate, the remaining water is squeezed out, and it becomes chalky. Iron and sulfur compounds in the yolk will start reacting to form a green ring.

When the time is done, transfer the eggs into an ice bath. The cold water pulls heat from the outer layers faster than it can move inward, which stops carryover cooking. This keeps the yolk at exactly the doneness you aimed for. If you want to eat them warm, just 1to 2 minutes in the ice bath is enough. For cold storage, meal prep, or a desire to eat cold eggs now… leave them in for 10 to 15 minutes to chill completely.

Peeling Technique

The easiest peeling method I’ve found is underwater peeling. Fill a bowl with enough water to cover an egg. Gently crack the shell all over on a hard flat surface. Be sure to crack the wide end where the air pocket will settle. Submerge the egg and work your fingers into the shell, starting at the wide end. Water will be pulled under the membrane, helping it slide away from the white. This method allows you to be very gentle, with the weight of the egg being supported by a neutral buoyancy, which is especially helpful for delicate soft boiled eggs.

An added bonus: The shells stay in the bowl instead of sticking to your hands or the kitchen sink. With other methods, the eggs need a rinse to remove small shell fragments, but here each one gets a bath while it's being peeled. They consistently come out of the bowl clean. If you want to keep the eggs warm while peeling, use warm water.

After plenty of trial and error, and many dozens of ugly eggs, I’ve found that getting the three T’s right - type, time and technique - is the key to perfect boiled eggs. Once you dial it in, you'll get your preferred yolk with an effortless peel every time.